San Juan Chamula cathedral where mystical Mayan beliefs have merged with those of their Catholic conquerors.

Left: Malcolm Lumming and the Schuberth C3 modular helmet underneath the Bienvendidos a San Cristobal de las Casas welcome sign. Right: The safest place to park motos in Mexico is right inside the hostel, which was offered at just about every place that had enough space.

Left: Malcolm Lumming and the Schuberth C3 modular helmet underneath the Bienvendidos a San Cristobal de las Casas welcome sign. Right: The safest place to park motos in Mexico is right inside the hostel, which was offered at just about every place that had enough space.

Zapatista paraphernalia goes mainstream with this colorful little store selling posters, lighters, pens, and masked, gun toting dolls in support of the ongoing indigenous farm worker’s rebellion.

Zapatista paraphernalia goes mainstream with this colorful little store selling posters, lighters, pens, and masked, gun toting dolls in support of the ongoing indigenous farm worker’s rebellion.

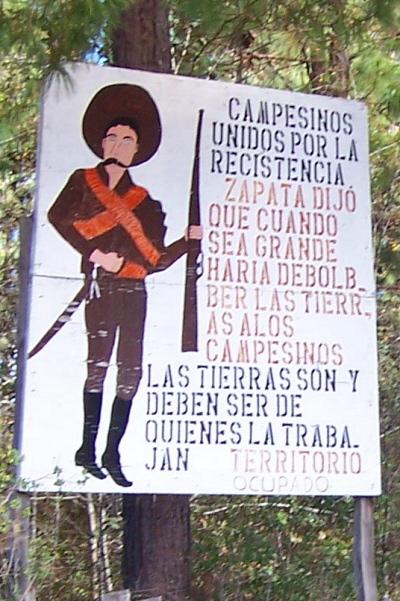

Roadside Zapatista sign descending from San Cristobal de las Casas: “Farm Workers United for the Resistance. Zapata said that when he gets bigger he would return the land to the farm workers. The lands are and should be of those who work them. Occupied Territory”

The stunning view from the top of the Toniná ruins and ex-ruler Jaguar Bird Peccary doing time on the front steps.

My cigarette lighter plug has proved to be an invaluable travel addition used to both power electronics as well as receive a charge from a battery tender I spliced to a cigarette lighter adapter to avoid having to “disassemble” to check or charge my battery.

At one point, when passing through a group of four young locals walking up a narrow part of the dirt throughway, I flipped up my modular helmet to say “perdon” when the young men jumped back as through they had seen a ghost. It wasn’t the motorcycle though, since Malcolm had passed just 30-seconds before, but seemingly the surprise of a woman on wheels in a place where traditional roles and restrictions remain.

On every non-toll road through Mexico, you’ll find marked and unmarked topes,

or speed bumps, oftentimes built by the locals to control speed that is

otherwise relatively unregulated. Mexicans tend to drive on the basis

that where there’s no enforcement, there are no consequences. I'd put money down that this barely visible 90-km straight-of-way bump has claimed it's fair share of bumpers.

On every non-toll road through Mexico, you’ll find marked and unmarked topes,

or speed bumps, oftentimes built by the locals to control speed that is

otherwise relatively unregulated. Mexicans tend to drive on the basis

that where there’s no enforcement, there are no consequences. I'd put money down that this barely visible 90-km straight-of-way bump has claimed it's fair share of bumpers.

The Jaguar Cabañas run by a Mayan family who spoke the traditional Quiché amongst themselves and Spanish to the rest of us main-streamers.

Nothing like 130-something volts flowing just inches above your wet head.

Stunning Usumacinta River float to the Yaxchilán ruins from Frontera Corozal.

The 1500 years of history emanate through the twisted vines and energy in the Yaxchilán ruins.

Touristic snap shot in front of the Welcome sign as we swung in for a beer on the Guatemalan side of the Usumacinta River.

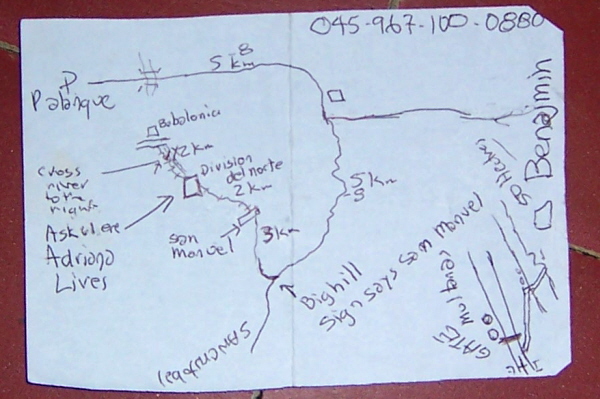

The hand-penned directions to the Escuela Reserva.

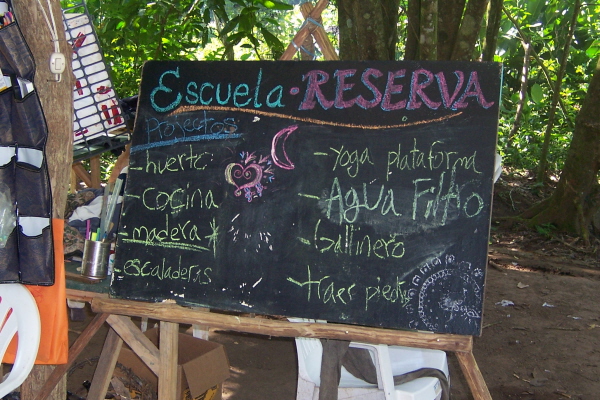

Along with the chicken coop, yoga platform and garden, the Escuela Reservists should add fire twirling or unicycling to their 'to do' list.

Looking down on the Temple of Inscriptions, mowed and well maintained ruins of Palenque.

Palenque's howler monkeys do give a crap!

Gourmet grasshopper gift baskets … hmm, makes you think twice about the chirping snacks outside your bedroom window.

Heading north along the Yucatán's turquoise Gulf Coast on the MEX180.

A protest outside the window of our Campeche Hostel. The

sign says: Anarchist Movement of Campeche requires housing support and

a solution for the elderly of Campeche.

Following the Google Earth plottd breadcrumbs through the papaya farms and down the brush lined backroads to the Uxmal ruins.

Ms. Pickles Uxmal oasis, The Pickled Onion, complete with restaurant, refreshing pool and camping.

Uxmal's light show vibrantly illuminates the intricate architecture of multiple buildings to a story about the trials of ancient Mayan life. Best watched with a copa de vino.

The curved corners of Uxmal’s Pyramid of the Magician and a hoop of the Mayan ballgame where the losers faced something a bit more ‘deadly’ than defeat.

Top: In mid-Mérida-jaunt we happened upon a theater performance of

cultural songs, costumes and dancing, including the traditional Mexican

Hat Dance. The doors were open and to our frugal surprise, we walked

right in and joined the other passersby for a free cabaret. Bottom: A street-side oil change is simple when you don't have to dispose of the old stuff.

Round one and two of three flats in a row on the side of the road, post new tire-n-tube pinch flat turmoil.

Round two at Mérida’s MotoMundo to flip the tread, change the tube and nut the valve stem … argh on this preventative failure.

We enjoyed lunch with a supreme 138-foot view from the top of Coba’s Nohoch Mul pyramid while being amused by the ‘athleticism’ of the bus tour tourists scooting their way down the stairs.

'If you can't find it, build it' is the awesome and inspiring ingenuity of Mexico.

Left: My 2008 KLR fitting right in at The Weary Traveler hostel in Tulum, Mexico. Right: Looking into Cenote Angelita before scuba diving down to pass throught the sulfer layer ay 92-feet deep.

Yucatán Twirl

Mapping ruin-to-ruin dual-sport routes through the Mayan World

by Brienne Thomson

We launched our journey by bombing down the mainland Mexican coast from the Lukeville, Arizona border crossing to shoot through the bloody territorial disputes between rival drug cartels (in association with a vast cast of corrupt-o-cops) vying for prime MEX-to-US smuggling zones. The month prior to take-off was spent elbow-deep in mechanical experience after a seized piston on his "KiLleR" preceded a sporadic loss-of-compression on mine. Two complete rebuilds later and weighed down with a ton of "what-if" spares, we were off to scope out unmapped dirt-roads to GPS a Mayan ruin-to-ruin tour as we horseshoed from west to east around the Yucatán.

From the Chiapas highlands of San Cristobal, surprisingly built-up with an AutoZone just beyond the historical district, we wound down 4,000-ft to the east past the Zapatista claimed lands on our Shinko 705 shod dual-sports into the town of Ocosingo. Our first ruin-rendezvous was just 12-km out of town. With a modest $41-peso entrance fee (12-pesos: 1-dollar), the Toniná Ruins were complete with an informative museum of Mayan artifacts, a grand pyramid with seven-stories of narrow hand-laid steps and a tribe of dreadlocked hippie kids smoking a doobie on the top. The breathtaking panorama was also a lesson in ruin exploration to always carry lunch along because everything tastes better with a view atop a 1600-year-old pyramid.

After absorbing the historical vibe of the site, and despite the sinking sun, we set out for the Bonampak ruins. This would be the first “let’s see if we can make it through” route I plotted using the extraordinary satellite images from Google Earth. We were riding waypoint-to-waypoint, guided by our waterproof Garmin Nuvi 500 GPS receivers that were bike-battery powered and connected with $10-dollar waterproof cigarette lighter receivers I found at a superstore chain.

Instead of taking the 230-km highway round trip to Bonampak, we headed east toward Monte Libano; the last major town mapped north of the impassable Lacandona Forest. The road turned to dirt early on near a town titled Monte Livano; note the “v” in place of the “b”. I simply thought it was a spelling error on the map – a common occurrence since third-world Latin America spells phonetically, which seems to vary from person-to-person and map-to-road sign – and that we had already reached Monte Libano, where I assumed the dirt began. But, as fortune had it, we still had miles to roost before Monte Libano as we curved through valleys of rural pueblos surrounded by a sharp volcanic-cut horizon line.

A few fun ruts, climbs and splits in the road kept us chugging along after sunset, when we followed our GPS-breadcrumbs down steep dirt road into the indigenous pueblo of Naha. I could see the moonlight glistening off a huge lake as we descended into town and knew that I should have made this a full day’s exploratory journey instead of an afternoon squeeze. I stopped to confirm direction with some locals sitting under a glowing yellow porch light and was directed to turn back and head towards El Jardin for a “more direct” route to Bonampak. This tells me that there certainly are more roads and more adventures to be had around the jungle of Lacandona.

The path eventually turned to asphalt as we neared the main road and was obstructed by the customary topes, or speed bumps, as we meandered through the tiny towns before hitting the highway and heading south toward the ruins. We hit the tourist-supported town of San Javier and followed signs that directed us down a dirt path to find a place to crash for the night. We creped our motos across PVC pipe constructed bridges, and were greeted by a dinky 4-foot-something Mayan woman at the rustic Jaguar Cabañas. The price was right and there was hot water – a rarity in these eternally hot-n-humid regions – fed from a suicide-shower; the kind with an electrical heating element in the head powered by varying 120/140-something volt wires, usually uncapped and twisted together just above the shower; hence the name.

The mini-Mayan, who said she spoke “Pura Maya” or pure Mayan, although it's not one of the 21 recognized Mayan dialects, gave us a tour of her art collection before we took off to tour the ruins. Just a few kilometers down the dusty road we arrived at Bonampak, meaning “painted walls”, but were told we needed to take a colectivo, or shuttle bus, the 9-km to the ruin site; no private vehicles allowed.

We negotiated the $70-peso ride down to $50 per person from a distinctive albino-esque looking local with blue eyes and reddish hair to see the most well-preserved murals remaining from the ancient Mayan civilization. Aside from this added cost on top of the $41-peso entrance fee, it was more nerve-wracking to leave my motorcycle in another country, fully packed, uninsured, and unsupervised … or at least unsupervised by me. The cost of international insurance coverage for such a long adventure is about the equivalent of the total value of my geared up ride – clearly ridiculous – and down here, probably about as effective as chewing gum on a pinch flat.

We rolled down the jungle engulfed trail to the remote site and saw the 1,200-year-old frescos of Mayans dancing, stealing and bleeding, while our driver waited in his van watching the ever-so-enrapturing telenovelas, or Mexican soap operas, on a built-in mini-monitor. Fortunately, for time purposes, Bonampak is a fairly small site and the hour limit we were allotted was just about enough.

We left the tiny junction town and headed a short 35-km towards Frontera Corozal; a border town on the Usumacinta River that divides Mexico and Guatemala. At the end of town on the river’s edge was the Escudo Jaguar, a hotel with an onsite boat-tour office that allowed us to camp and use their shared bathroom facilities. Frontera Corozal is the home-base for Yaxchilán (ya-she-lawn), one of the most isolated ruin sites on the Yucatán. It sits on the Mexican side of the river in the midst of thick jungle, and is not connected by any roads or trails; just the river.

The hour-long float to Yaxchilán was more than an A-to-B passage; it was a jungle boat tour in itself. The cost was based on quantity, so the previous night I found some other tourists to share the expense with; a couple from Cancun along with his American parents and sister from the east coast. We paid $100-pesos per person on top of the $49-peso tickets.

Arriving at Yaxchilán is like transporting yourself into “Where the Wild Things Are”. The surrounding jungle was webbed with twirling vines, tropical bird calls and a spectacular chorus of howler monkeys swaying together to their thunderous hoots and grunts. In the darkness of the 1,550-year-old stone structures, squeaking bats hung like festoons from the mossy ceilings and the history and mystery of the site was palpable.

And while some tourists catch a ferry to the site from the Guatemalan side of the river, we just stopped over to have a beer and give the South Carolina mom-n-pop duo a chance to claim that they had been to Guatemala: amusing tourist photos in front of the “Bienvendidos a Guatemala” sign followed.

While chatting about our ruin-route with the Cancun-couple, we were invited to crash at their Palenque-close permaculture farm that was occupied by the Escuela Reserva. They gave us directions on a hand penned map that entailed opening nine gates as we passed through private farms, turning at the two big red trees down a trail and if we got to the next village, we went a kilometer too far. For a free night of camping and enticed by the backwoods location, we were on our way.

In the first village of San Manuel, before the barrage of gates, we decided to stop in at a grocery to buy a few vegetables. We arrived in the dinky town of a couple hundred, and after walking into the first little roadside shop, they came; kids, hoards of kids. Speaking in both a Mayan dialect and Spanish, they peered at us through the one-room store window and surrounded our bikes. Although they were only about 25-km from the busy town of Palenque, they had probably never been. There were very few cars around and the only other transport out was by the colectivo; a canvas-covered pick-up truck shuttle used mainly by farm workers – at least the ones who weren’t carrying their daily harvest on their backs. The first shop had no vegetables or tortillas, but when we asked about where we could find some, a man gestured to his wife to run home and fetch a few. After paying a “foreigner” tortilla price and after my 'who/what/why we were there' speech I felt compelled to give being that we were the town spectacle, we were directed to another tienda just two tiny dirt blocks away, that “might” have some vegetables.

Down the dirt road and around the corner we encountered a second shop and inquired. The owner said that he had no vegetables and that there were none available in the town. He did try to entice us with other options, but when I looked down the road I saw a cardboard box lid with “Tomate” written on top. I rolled the 30-feet forward and found a fully stocked fruit-n-vegetable store.

In such a minuscule little town where the majority of the population is probably related – in more twisted ways than marriage – I was surprised to see the cousin-in-laws being so competitive as to lie.

The good thing we learned from the San Manuel locals is that we’d find the trail down to the permaculture farm near a white truck. We tag-teamed our way through the gates, down the rutted road, around the cow pies and through the cows themselves and finally came upon the white truck and its hippie-go-lucky owner, Luis. He took us down the trail and showed us our crossing options for the stream that divided the camp from the road; we could walk across on unstable round-rocks in knee-deep water or pull ourselves over it on a big swinging cart. Since everything has a specific place in moto-luggage, meaning that picking out an overnight bag would be more tedious than muscle-hauling the whole lot of it, we chose the latter and pulled our way across to the other side. As we arrived, a gang of dreadlocked, charm wearing folks and their instruments kissed us hello and goodbye, mounted the crossing cart and, in a waft of some pungent herbal essence, were gone.

We met the remaining seven Escuela Reserva members at the gathering table after we set up camp. They told us about their days of toiling on their self-sustainable farm, while they rolled chocolate balls to sell to Palenque tourists. They were from all from different countries; Germany, France, Canada, Argentina, Holland, the United States and Mexico, and had come across the Reserva recruits through random encounters or through the WOOF (World Wide Opportunities on Organic Farms) volunteer organization. We chatted as we enjoyed our “taboo” tuna taco dinner at the vegetarian co-op, while the reserved Reserva students sipped their homegrown soup before gobbling down the extra tortillas we offered with carb-starved speed.

Although the jungle enveloped swimming hole and learning more about this international hippie commune were enticing, we decided to get the stop-n-go gate trek over with in the morning and continue on our road of ruins. The group did suggest some Palenque-close cabañas to crash at where they’d be meeting their didgeridoo drum tapping band buddies and selling chocolates. So, following advice from fellow wanderers and, of course, my undefiable taste for chocolate, we motored to the cabañas in El Panchan and set of for Palenque.

As forewarned, the Palenque ruins were indeed touristy, but the structures, temples and stone carvings were intricate, massive and well maintained. From carvings of Mayan writing, which consists of intricate glyphs of facial expressions, animals and designs that convey different meanings, to a 700 AD aqueduct system constructed to divert an abundance of water as opposed to collect it, Palenque was well worth the journey.

On par with the historical draw of Palenque, although in a whole different genre, was the unsigned jungle engulfed backpacker zone of El Panchan that lay just before the entrance to the Palenque National Park. We stayed at Mono Blanco, one of the many intertwined hostels, to see the Escuela Reserva hypnotic-hippie band’s evening performance. However, it wasn’t necessarily the slow beat of the rosewood rhythm sticks or tambourine that caught my interest, but the Cirque du Soleil-esque acrobats twisting their bodies up and down ribbons strewn from the roof – apparently one of the many artsy acts El Panchan has to offer. Late into the melodic night, we retired to our little dwelling about 50-meters away from the stage and woke to find that a howler monkey had dropped a little present on Malcolm’s moto and our hippie-go-lucky friend who cashed in our extra bed had disappeared before sunrise.

It was time to blow through Palenque’s cloud of patchouli and head for the northeasterly off-highway route towards the Gulf. The dirt route through the pueblo of La Libertad proved to be pretty interesting, taking us through little farming villages and landing us at an “Artisanias, Gastronomia, Actividades Culturales” street fair in Emiliano Zapata for lunch where I tasted my first crunchy, chipotle-flavored chapulin; aka grasshopper. It was certainly worth a nibble, but I passed on ordering it for the lunch special.

We tested another satellite plotted dual-sport route on our way toward the gulf-coast town of Sabancuy that was an unfortunate farm-gate failure. But we continued around and arrived on the northern Yucatán coast, paralleling the Gulf of Mexico. The waters became a vibrant tropical-turquoise and the libre road windy enough to see sportbike riders enjoying the twisties. And I’m talking US-sized machines, not the south-of-the-border 125cc scooter-sized standards, but Triumph Triples, GSX-Rs, Ducatis and such a variety of sporty power that I though it might be a magazine test.

Pausing in the coastal city of Campeche, a community that proved to be quite invigorated with cultural pride and preservation by hosting weekly concerts and dance performances under their central plaza’s white gazebo, we found the Monkey Hostel from where we could see it all. And interestingly enough, the next morning, while scouring the internet for the elusive 130/80-17 rear tires we needed, the hostel’s balcony also became the prime viewing point for a plaza protest.

It took a couple days of online searching, e-mailing and phone calls, to locate the only in-stock dual-sport tires between Campeche and Cancún in the Yucatán’s big city of Mérida. We modified our route to continue east to Mérida, since ordering them to a Kawi-dealership in Cancún would not only take a minimum of two-weeks, but also cost $250-dollars per tire, compared to the Kenda K761 we found for $118-dollars at MotoMundo in Mérida; although, still double the price of comparable rubber in the States.

We left Campeche and headed up the highway toward my ruin-route waypoint before continuing to Mérida. We turned off onto the dirt, twisted through papaya tree farms, down rocky, rutted pole-line roads and popped out on pavement along side the Mision Hotel just minutes from the Uxmal Ruins (oo-sh-mal). However, since the onsite inns were well out of our backpacking price range, we continued the 14-km to the small town of Santa Elena. After a few price-checks we found The Pickled Onion, a stunning location with a restaurant and pool owned by a British woman, Ms. Pickles, who let us camp and soak for just $50-pesos a person.

That afternoon we headed back to Uxmal to find the most pricey ruin tickets yet; $51-pesos for the entrance tickets and $115 for tourist taxes. As income-less wanderers this was both a bit above our planned budget and, based on principal, tourist tax extortion. We motored back to the Onion oasis and had a chat with Ms. Pickles who explained that the tickets were also good for a nighttime light show and that Uxmal was superior to the tourist trampled ruins of Chichen Itza; an opinion I had heard before.

So, with a to-go flask of wine, we splurged and found our seats under the warm starry night sky to watch the ancient ruins illuminated in purples, blues and reds to the thunderous story about the plight of the Mayan people facing war and drought and royal weddings … in Spanish, of course. When the show ended, the ruins disappeared in the darkness, making the following days Uxmal exploration even more enticing.

After a day wandering the vast iguana-packed grounds of Uxmal, a fancy top-o-pyramid lunch and a couple extra nights soaking in Ms. Pickle’s pool, we took the 96-km tire trip to Mérida. After searching through the slow city traffic we landed at Hotel Aventura, just a five-minute walk from the central plaza for the modest price of $300-pesos a night. We unloaded our moto luggage and strolled through the vendors of trinkets and food and street shows before meandering down the pedestrian way, ice cream in-hand, past the live bands and people-watching bleachers setup on the sidewalks.

In contrast to our evening, the following day commenced a vicious round of moto-mayhem, beginning with finding the motorcycle shop. Since each little district within the larger city of Mérida has a Calle 36, we struggled to find the precise one that housed MotoMundo. When we finally arrived, to our happy surprise, our Shinko 750 replacements were set aside waiting for our arrival. And oddly enough when we said we could mount them ourselves, our service fee was waived even though the service wasn’t … sounded good at the time. The next morning we followed up our fresh rubber with some fresh oil that we bought from BiciMotos, a shop just a couple blocks from our hotel, who let us use their oil containers to do the swap ourselves. It’s so freeing to be in a country that doesn’t live in fear of lawsuits, as compared to some service centers in the States I’ve encountered that were afraid to lend me a wrench.

With new tires, fresh oil and clean chains we felt so maintenance-accomplished, but then – dun-dun-dun – 100-kilometers down the highway, mid-Yucatán Peninsula, I started wobbling. I thought I was feeling the new tire getting scrubbed in or its shorter profile that flattened out my bike’s geometry. But, when we stopped on the shoulder of the Y-split to confirm whether or not to take the libre or cuota road, I sank. All of the time and money spent in an effort to prevent flats became futile. I was now feeling a bit jealous of the big-buck-bikes, like the BMW GS rides that have PSI sensors in the wheels with digital readouts on the dash – not that it would have prevented anything, but forewarning would have been nice.

Off came the luggage, out came my spoons, off came the tire, out came my Genuine Innovations tube patches and CO2 cartridges … reverse the aforementioned actions, add 45 minutes to the clock and we’re back on the road. It was a post-seating pinch flat, exacerbated by the fact that there was no nut on the valve inside the rim to prevent tube movement.

We chose to take the cuota road, despite the exorbitant fees, because of the Green Angels; a free emergency service that patrols toll roads, brought to us by the Ministry of Tourism. And just a couple hundred meters down the road, I needed one. I was on flat numero dos. My patches weren’t big enough to sufficiently cover the three little holes-in-a-row and my emergency tub was a 21” front that was to be used in the rear for emergency purposes only. But just then, Angel Alex, with his little green pick-up pulled up behind us.

He took me to a llantera or tire service center. However, it was closed on Sundays, so we ended up at a bicycle repair hut. The tire guy walked out from underneath his unsigned backyard workshop palapa and without hesitation, patched my tube. The process entailed finding the hole in a tub of water, roughing up the surrounding area for better adhesion, sticking the patch on and using a pizza wheel to ensure it stuck.

I tipped my Green Angel and thought I had a great temporary fix until I found a new tube, but I was mistaken. Transport me another 20-km down the cuota road, rewind the story above, push repeat and watch a different tire guy remount my tire with a flat-head screwdriver.

It’s now dark. Malcolm had been waiting for well over four-hours on the side of the road and we’re finally on our way to a run-down hotel in Piste, a Chichen Itza backpacker’s hub, despite our plan to bypass the tourist-swarmed “wonder of the world”.

As I sipped a cup-o-vino on a Posada Maya hallway table, watching the cucarachas trot by, I chatted with a fellow guest from France about my terrible tube trials. In his heavily accented Spanish, he mentioned the difference between my tire and Malcolm’s. Mine, he noticed, was mounted backwards … gulp, my jaw dropped. I think the blow to my self-purported keen sense of observation might have been audible.

Since such wide 17” tubes were so few and far between, I felt that it would be more expedient to take the three-hour round-trip back to Mérida's MotoMundo so they could set things right and give me a fresh tube. We squeezed onto Malcolm’s bike, so as not to chance the trice-patched tube and took off retracing our tracks.

MotoMundo replaced my tube, turned my tire and added the internal rim nut on the valve stem that they had forgotten at no cost. They also checked to see if Malcolm’s tire had an internal rim nut, which he apparently did, despite having two exterior nuts; go figure. We puzzle-pieced ourselves back on the bike along with my tire and headed back as the sun set on another full day of tire yah-yah.

Forty-kilometers down the libre road, we continued our Mayan ruin-rounds at Cobá. After a 4-km hike around the expansive site, as the bussed-in tourists were pedal-pushed past us in bici-taxis, we climbed the main pyramid for our lunch-with-a-view. But not only did we get a 360-degree view above the treetops, but we also saw a surprisingly widespread fear-of-heights in action as the majority of people ass-scooted themselves down the main pyramid stairs, which really weren’t much steeper than a staircase. Of course, this spawned a reaction to amuse ourselves by taking pictures of them and two-step our way down the pyramid as we blew by them.

We spun into the beach-front city of Tulum on the southern Yucatán coast that evening and planed to end our loop with a treat and scuba dive the Cenotes. Cenotes are massive water filled holes leading to miles of caves throughout the eastern Yucatán Peninsula. They’re credited as the source of Mayan hydration and were allegedly created by the meteor that killed the dinosaurs. The Cenotes were decorated with stalactites and mites after the first ice age melted away, and subsequently filled with freshwater after the second ice age liquefied … to give you a brief history of one of the “wonders of the underworld”.

About a kilometer from the hostel in Tulum my reserve kicked in at its usual 200-miles, which is about 15-mpg less than the 55-mpg advertised for the 2nd-generation KLR’s 6.1-gallon tank. So, we swung into a PeMex station, a government-owned fuel monopoly, to fill up. But as Malcolm went to remount his ride, it too sank to the ground; another post-new tire flat. Where did we go wrong?

We presumed that it might be a max-load weight issue. We have 410-pound bikes, 100-pounds of gear, 135/180-pound riders and a rear with a max load of 640 with two-tires to absorb the weight. This should be within limits.

Since Malcolm's leak was slow, I filled his tire and told him to burn rubber to the hostel so we could have a place to park and sleep while we patched the problem … yet again.

The next morning – day-four of tire tragedies – we went to yet another llantera. The man replaced Malcolm’s tube with a new one he bought from MotoMundo (the only one available) and patched the old one for emergencies, using the same pizza-cutter adhesive method.

On top of the tires, we had two more moto-mechnicals to overcome. The rear axle nut on Malcolm’s KiLleR had been over-torqued and stripped and my spare front brake pads miraculously converted themselves into 1st-generation KLR rear pads. Although, a ridiculous online pre-trip shipping mix-up is the more likely culprit. But, here’s where I discovered the ingenuity of the 3rd-world.

“If you can’t get it, make it,” said the owner of Casa del Sol Hostel in Tulum when I vented about our mechanical mishaps.

He directed Malcolm to a machinist who threaded a new bolt to fit his axle and me to a brake shop where the machinist removed the remaining slivers of my front brakes and riveted on new pads cut from a reel of brake-shoe material for cars. This was, of course, after a day of driving an hour north to the larger tourist enclave of Playa del Carmen where the only way for me to get brakes was to order them, pay $35-dollars, wait a week and make a return trip to pick them up. The custom fit brake-shoe pads cost me $8-dollars, were ready in an hour and work just fine; mayhem-regulated.

After overcoming the many moto-mechanicals, testing unmapped dual-sport routes, logging 1615-km and experiencing six mystical Mayan ruin sights in 25-days, it was time to relish in the achievement and enjoy the white sand beaches of Tulum.

If other world wanderers are thinking of taking a Yucatán Twirl, click here to download the .gpx file of this adventure to use, improve and revel in themselves.

As plentiful as Central Park pigeons, this Uxmal Iguana soaks in some sun.

Detailed Mayan carvings and spacious views at the Uxmal ruins in the Yucatán.