Photo: Rancho Boyeros, Cuba, November 2015, taken by Derek Dutt

Introduction:

For the past 56 years the Cuban people have been living on the Castro stage of a utopian dream, marred by an international political game of arrogance and exclusion. What was stated as the initial objective of Fidel Castro’s Cuban Revolution, to give freedom to his fellow countrymen, mutated into a communist dictatorship that was sustained by isolationism, soft-power through propaganda, and shuffling the blame for self-preservation. Castro initially constructed his following through his flair of charisma and communication – obligatory for a revolutionary – and used these traits to build an internal media empire and control information flows to the 11-million Cubans living under the Party of Communist Cuba (PCC).

After the end of the Revolution in 1959, followed by 30-years of economic dependency on the Soviet Union, the USSR’s collapse in 1991 sent Cuba into a tailspin, forcing them to rebuild from the ground up. This “Special Period” was a devastating time where attaining the basic necessities of food, healthcare and shelter took precedence over implementing any technological progression, even though the .com boom was simultaneously sweeping across the United States, just 90-miles to the north. This period incited an extended pause for Cuban modernization and forced them to restore their economy and humor.

In 2008, at 82-years old, Fidel Castro relinquished the presidency over to his younger brother Raúl, 5-years his junior, and for the first time, stepped out of the limelight. Since Raúl has been in power Cuba has seen great reforms and the loosening of restrictions on foreign investment, international travel, and the right of private ownership; from computers and cellphones to micro-enterprises. However, one of the most essential topics that has yet to be relinquished by the PCC is the censorship of communications and the fear that granting freedom will be their downfall.

Thus, the incorporation of the internet and how to go about instituting accessibility while preserving power is the “conservative dilemma” the Castro government is currently facing. [14] This essay analyses the soft-power Fidel and the Revolution absorbed from the Cuban people through the media megalith he erected, and questions the effect the resulting bias might have on the Cuban people once they gain access to the internet. Will ‘tribalism’ be established via social media and lead to dissent? Or, will the appeasement evoke nationalism? This is, of course, pending the communist regime grants this freedom.

The Stage:

After being released from prison and fleeing to Mexico in 1955, post-attempted coup to oust the repressive military dictator Fulgencio Batista, Fidel Castro, his brother Raul and the famed Argentinian doctor turned revolutionary, Ernesto “Che” Guevara, planned their strategy and returned to Cuba to launch a bloody gorilla revolution that lasted until January of 1959.

But the alleged objective of Castro, to give freedom back to the people of Cuba and establish a democracy, seemed to deteriorate as a result of an external actor; specifically, as a consequence of malicious dealings with the United States that instigated Cuba to align with the Soviet Union. Regarding this charge, however, there is controversy in the literature as to whether Castro was hiding his objective to establish a communist government during the revolution, so as not to antagonize the United States, or whether his alleged democratic plight was transformed by Cuba’s dependency on the Soviet Union for economic stability as an importer of Cuba’s sugar and supplier of oil.

Either way, Cuban politics slid all the way toward the left, transitioning into a communist dictatorship and setting the stage for Cuba to be the Eastern Bloc’s outlying western member; the Eastern Bloc having been an economic union of mainly eastern European communist countries. Thus, as a “dependent” ally to the Soviet Union, and having already been embargoed by the U.S. just one-year prior, the Island of Cuba also became a launch pad for Soviet nuclear missiles during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis.

So, with the tensions exacerbated between Cuba and the U.S. superpower, just 90-miles beyond the sea to its north, Cuba has lived in self-preservation mode for the past 54-years. And with the same objective as preserving a filet of fish – to maintain something in a state so as to resist decomposition – the Castro regime’s “salt,” or method to maintain and regulate its domestic and international reputation, was to establish strict control over information flows. [14]

Either way, Cuban politics slid all the way toward the left, transitioning into a communist dictatorship and setting the stage for Cuba to be the Eastern Bloc’s outlying western member; the Eastern Bloc having been an economic union of mainly eastern European communist countries. Thus, as a “dependent” ally to the Soviet Union, and having already been embargoed by the U.S. just one-year prior, the Island of Cuba also became a launch pad for Soviet nuclear missiles during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis.

So, with the tensions exacerbated between Cuba and the U.S. superpower, just 90-miles beyond the sea to its north, Cuba has lived in self-preservation mode for the past 54-years. And with the same objective as preserving a filet of fish – to maintain something in a state so as to resist decomposition – the Castro regime’s “salt,” or method to maintain and regulate its domestic and international reputation, was to establish strict control over information flows. [14]

The power of information and how to employ propaganda was nothing new to Fidel Castro; as it is undoubtedly on the ‘required skills’ checklist for any revolutionary. During his attempt to attract soldiers domestically, he and Che established a small newspaper, El Cubano Libre, as well as a radio station, Radio Rebelde to disseminate their ideas. [6] To gain support internationally, while in the midst of batting Batista, Castro also gave interviews to the New York Times and CBS, appealing to U.S. values and upholding a seemingly fallacious narrative about his democratic intentions in order to garner American approval.

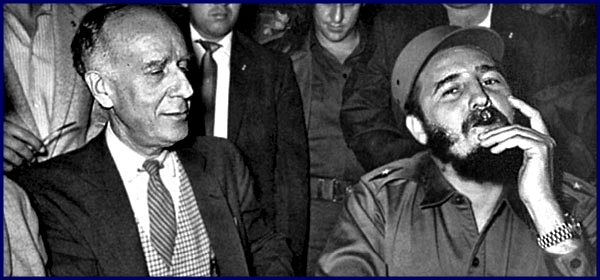

Herbert Matthews, New York Times author of the 1957 article “Cuban Rebel is Visited in Hideout,” sits with Castro during his trip to New York in 1960. This photo was found in a New York Times Sunday Book Review from April 2006. The reviewed book, by Anthony Depalma, is titled, “The Man Who Invented Fidel.” Although, I would modify it to more appropriately read, “The Man Fidel Manipulated to Invent Himself.”

According to “Castro’s Propaganda Apparatus and Foreign Policy,” a CIA report that was released 20-years after its 1983 ‘internal’ publication through the Freedom of Information Act, New York Times reporter, Herbert Matthews, is exemplified as one of the many information intermediaries who was manipulated through a 1957 interview he conducted with Fidel. The “Propaganda Apparatus” article notes that when talking about his revolutionary support, Fidel, “overstated the strength of the insurgent band (thanks to Castro's deliberate efforts to deceive Matthews), and gave the insurgents vital international exposure. Castro's comrade-in-arms, Che Guevara, recalled two years later: ‘At the time, the presence of a foreign journalist, preferably an American, was more important to us than a military victory.’” [5]

Che noted that the New York Times exposure was vital because it resulted in support, funds and fighters that were essential to Castro’s insurgency. [6] Apparently, the three pro-revolution fashioned front page stories that were based on Matthews’ interviews induced a “rebellious romantic idealism” – three of the common interview response adjectives – that melded with the radical defiance of the 1960s. [1, 5, 9]

But even more important than appealing to the youth was Castro’s quote insisting that his aim was to topple the dictatorship and restore “a democratic Cuba.” Castro’s denial of communistic ideals was dire in order to gain U.S. support, especially from a country just recovering from the McCarthy witch hunt, while on the verge of sending troops to fight against the communist takeover of South Vietnam. [10]

After five-years of fighting and psychologically wearing down Batista’s soldiers, which effectively influenced many his troops to refuse to fight the rebels, Fidel, Raul, and Che marched into Havana at the break of the new year, 1959. They took control of the government and appointed a liberal lawyer, Manuel Urrutia Lleó to be president. But despite Urrutia having vehemently opposed Batista during his final campaign – which deteriorated into Batista hijacking the presidency through force – Urrutia’s pro free-election and anti-communist stance rubbed Fidel the wrong way, making his presidential position rather fleeting; a 6-month stint, to be exact.

And in April of 1959, just two-months before Urrutia relinquished the presidency and fled for the United States, in heavily accented English, Castro told NBC's Meet the Press:

“I am not communism. I am not agree with communism. … Free press to everybody, free ideas, free religion belief and all those rights, those human rights that we could establish. … What we want to get as soon as possible the condition for free election,” he appeased. But he also added, “As more people help us and more we be understood, the more fast we can solve our problems and the more fast will be the elections.” [12]

There was obvious discrepancy between the reasons behind Urrutia’s quick departure and the alleged principles Fidel was feeding the United States. To maintain this narrative, Castro’s provisional government continued to build up their “propaganda empire” that the CIA subsequently noted to be “perhaps the most effective in the hemisphere,” being that it had also established worldwide connections. [5] Although, it wasn’t for another three years post-revolution, in December of 1961, that Castro publically confirmed his political stance and introduced his Partido Comunista de Cuba (PCC).

To this day, all Cuban media outlets are government controlled and censored to the point that it is even prohibited to criticize or contradict business directors or country leaders; a stipulation in work contracts where, in Cuba, the employer most always is the government. [9] Thus, with no lawful independent media organizations,* the Cuban government has built quite a local and international brand through radio, television, websites and organizations that work to broadcast a narrative of support for communist ideologies. And, from personal experience, Cuba’s international reach is indeed extensive. As a Peace Corps volunteer in Paraguay from 2013-2015, I was able to pick-up a Spanish broadcast of Radio Habana on my shortwave receiver; although, according to the Cuba.cu outline of their media sources, Radio Habana (circa 1961), as “The voice of friendship that circles the world,” is also broadcast in English, French and Portuguese.

*Activist and blogger Yoani Sánchez launched an uncensored Cuban news site, 14yMedio; 2014 for the year of launch and “medio” means “media.” However, the site is blocked in Cuban WiFi centers, is registered in Spain and many postings are still done via USB-drives and proxies. [13] As well as 14yMedio, which made a big splash internationally, Freedom House’s 2015 Freedom of the Press report notes that domestically, underground newsletters and file sharing through USB drives is the modus operandi for acquiring clandestine information.

Many of the Cuban government’s .cu sites have linked tabs and dropdown options titled “Cuba vs. Embargo,” “Reflections of Fidel Castro” and “Discussions of Raul Castro,” including Radio Habana, RadioHC.cu, Granma, the “Official Voice of the Communist Party” (written in English), and Radio Rebelde, the station founded in 1958 by “El Comandante Ernesto Guevara.” And while it is apparent through Cuban media that the embargo is strongly opposed by the government, it is also seen by some as paradoxically supportive of the regime. The embargo has been touted as both an excuse for failures of the PCC, using the United States to blame for preventing access to resources, and has also been criticized as an enabler for the half-century of undisputed power the Castro regime has held through keeping the Cuban people isolated from news, information and travel. [1]

Homepage banner for Cubavisión Internacional found at Fidelista-Por-Siempre.org. Founded in 1986, Cubavisión is a very nationalistic themed TV station, where there is a 24/7 live stream that is also being beamed via satellite to 54 countries. [11]

So, after 56-years of being inundated by messages and propaganda reinforcing the Castro regime’s proclaimed humanitarianism, egalitarianism and anti-imperialism, there are, of course, many Cubans who continue to adamantly support “the revolution” – a term that has evolved to signify the Party of Communist Cuba (PCC). Recently, a Mexican/American acquaintance who did some contract work in Cuba in 2011, recounted how he rented a room in a bed and breakfast in the town of Cienfuegos. He mentioned that the older couple who ‘owned’ the house slept in a tiny backroom while renting out the other three bedrooms to tourists.* He added that, even though the couple had to pay an elevated fixed tax from their Cubano Convertible (CUC) tourism earnings to the government for the legal authority to rent rooms, they still proclaimed to be Fidelistas, in support of the revolution. However, the rationale behind PCC support, whether influenced by propaganda, fear or choice, is undiscernible.

*While renting rooms in Cuba has been legally sanctioned since 1997, the buying, selling and private ownership of property was only recently authorized in 2011.

With decades of government controlled media and sanctioned books, the propaganda factor is apparent. And, along with the threat of castigation for being an anti-revolutionary or speaking out against the regime as previously cited, Cubans who were homosexual, Jehovah's Witnesses, or those “accused” of crimes were also sent to labor camps; thus, the fear factor was another persuasive reason to abide the PCC. [2]

Regarding the topic of earnings and tourism, it is important to mention that there are two currencies in Cuba. The Cubano Peso (CUP), the money citizens earn via the government dole, is valued at 25₱ to 1 USD, or approximately 4-cents to the dollar, whereas the Convertible Peso (CUC) is fixed to the dollar at 1:1.

The “Convertible Peso” demarcation has been circle in red above to point out the importance of currency separation in Cuba, since confusion could be the difference between $2 and $50.

On a more positive note, there were some achievements under the communist party, as ephemeral as they were, where even the poorest of children were fed, educated and provided healthcare. The older generations who experienced this, mainly in the early 1980s, may have been justly won over by the revolution. However, this egalitarian dispersal of resources did have its shortcomings. Due to the inability for the island to be completely self-sufficient, a lot of goods had to be imported and dispersed, leading to perpetual ‘bread lines’ of Cubans waiting to receive the remaining goods. But, throughout the 80s, at least there were goods.

An incident on the other side of the world that brought Cuba to its knees was the collapse of the Soviet Union. As an economic dependent on the Soviet Union, the loss of exorbitantly priced sugar exports in exchange for oil left the Cuban island adrift.

“The disintegration of the Eastern Bloc led by the USSR at the end of the eighties represented for Cuba the loss of 85% of its trade and financial links with the rest of the world, and in consequence, the beginning of an unprecedented economic crisis. The resulting data is overwhelming. In particular, between the years 1989 and 1993, the total volume of exports fell by 47%. At the same time, the import capacity decreased by more than 70%, which severely affected the provision of raw materials, machinery and fuel. The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of the country suffered a contraction of 34%. [17] (Translated by Brienne Thomson)

This devastation sent the Cuban economy and people back to square one. The remaining trade, income, imports, and fuel couldn’t sustain transportation, tractors, or machinery, causing a food crisis and forcing many Cubans to revert to oxen and bicycles. This was deemed as the “Special Period” in Cuba, when life was bleak. It is also one reason explaining why the technology and telecommunications infrastructure in Cuba, sporting a 1991-vintage 2G mobile-phone network, is so antiquated when compared with global market availability. [8]

It wasn’t until 1999, when Venezuela elected a president with likeminded communistic ideals that Cuba was able to hash out a beneficial trade agreement, resulting in Hugo Chávez shipping billions of dollars in subsidized oil to Cuba. [9] In furthering this Venezuela/Cuba accord, a 2006 agreement was signed that launched efforts to lay an undersea fiber-optic cable and connect Cuba to the internet via La Guaira, Venezuela. [3] However, even though the fiber-optic cable plan was signed two years before Cubans were even allowed to own computers, it still wasn’t accessible until 2013.

Timeline Note:

In 2008, Fidel Castro stepped down from his 49-year dictatorial reign and was succeeded by his younger brother Raúl. Since this transition of power, Raúl has cracked open Cuba’s window to the world; allowing for privately owned micro-enterprises, foreign investment, and limiting the number of five-year presidential terms to two. This means that Raúl will step down in 2018, although, the possibility of an ‘election’ remains to be seen.

According to a timely and comprehensive blog titled, “The Internet in Cuba,” started in 2011 by Dr. Larry Press, a professor of information systems focusing on internet policy and technology in developing nations, the U.S. embargo has played a preventative role in establishing internet infrastructure in Cuba.* Apparently, some of the equipment needed to lay the ALBA-1 undersea cable was made by a U.S. company, effecting the candidate contracted to fulfill the Venezuelan/Cuban contract. The selected team was formed from three state-owned enterprises; China’s Alcatel-Lucent Shanghai Bell (ASB) and Telecomunicaciones Gran Caribe (TGC), a joint venture between Telecom Venezuela and Transbit de Cuba.

*According to Freedom House’s 2015 “Freedom of the Net” report on Cuba, “In March 2015, the Nauta intranet banned Larry Press' blog, The Internet in Cuba, one of the best sources about the Cuban ICT sector.”

And despite 2014 repealed restrictions from the Barak Obama Administration that allowed for U.S. telecommunications companies to work with Cuba, Raúl Castro’s regime has instead turned to Chinese companies to connect the island nation. It was, in fact, China who financed the construction of the ALBA-1, lending Venezuela $70 million. [15] Dr. Press’ blog also mentions that even with the completion of the cable, the poor domestic telecommunications infrastructure limits high-speed access from the cable’s landing site on the east side of the island to larger metropolitan cities. This means that for even those with internet access, downloading and streaming are features that remain on the broader side of the available bandwidth ceiling.

While there are 118 national “navigation” centers for public internet access, in July of 2015, 35 broadband WiFi hotspots were added by the Cuban Telecommunications Company, La Empresa de Telecomunicaciones de Cuba S.A. (ETECSA), to allow Cubans to surf the web with faster access. Thus, after purchasing a “Nauta” access card for a measly $6 CUC that comes with one-hour of access – a required investment whether accessing the Nauta internet system from a hotel or ETESCA navigation center – users will still need to pay an hourly rate of $2 CUC to recharge the card. [7] Launched in March of 2014, Nauta is the name of ETECSA’s internet service as well as the @nauta.cu email, which is required for Cubans to send international email. Not only is Nauta access complicated with different access fees; for the national or international usage, and with or without e-mail, but it’s a pretty penny when the average income is 584₱ or $23.36 CUC per month. [16]

So, while Cuba is currently working with the Chinese multinational telecommunications giant, Huawei, to improve national infrastructure and the smart phones available through ETESCA, Cuba does not censor to the extent of the Great Firewall of China. Aside from the requirement to login for internet access and Cuba’s e-mail surveillance – evident based on the fact that a .cu email is the only way to get your message across the border – Cuba’s site censorship is minimal compared to fellow governments that suppress free speech. Censorship in Cuba generally includes anti-Castro and adult websites, as well as Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) sites, like Skype; although, the outdated infrastructure provides more of a blockade for multimedia communications. As of now, the inaccessibility is doing a fine job of censorship for the government.

Cuba is working to improve its telecommunications infrastructure and has big plans to increase internet access to schools and homes, but with a government founded on appeasing and restricting the masses to maintain loyalty, its method of delivering such a ‘disruptive’ technology that with dually appease the demand for an open internet and prevent social media tribalism from backfiring against them, looks to be a risky endeavor.

Currently, Cuba is dependent on Huawei and its international partners, mainly China and Venezuela, to accomplish its connectivity goals. However, Cuba is in debt to China, while its oil supplier, Venezuela, is facing an economic and political crisis. Meanwhile, on top of the structural foundation that remains in the works, Cuba also has the lowest rate of cellphone users of any Latin American country, at 22%, due to the inaccessibility of technology and the fact that Cubans were banned from mobile phone usage before Raúl took over in 2008. To compare figures, Haiti has approximately 1-million less people and 4.2-million more cellular users, according to 2015 International Telecommunications Union statistics.

Thus, in regards to technology, it seems reasonable to hypothesize that computer savvy Cubans are a rarity, but that’s not to downplay the demand. Cubans have been creating their own clandestine networks through file sharing with USB-drives, as well as making mini-intranets with Ethernet cables strung from rooftop to rooftop. But with Cuba’s internet surveillance through user tracking and .cu e-mail restrictions, they are also inciting people to build these underground networks of illegal modems and look beyond the borders for blog hosting servers. This brings up the “Conservative Dilemma” that Cuba is fostering between these Ethernet connections. According to “The Real Cyber War” authors, the Conservative Dilemma is when a non-democratic government “is confronted with widespread social protest, it has four options for restoring control: propaganda, censorship, total information control, and violent repression. Each choice entails risks—thus the dilemma.” [14]

But these dictatorial “choices” are only measures to assuage the people, which, as we’ve seen, can only be pushed so much before they “spring” forth with a vengeance. So, why not give them what they want? A shared satisfaction and happiness can be just as unifying as fear. And as egalitarian and endowing as the Castro regime feels it has been for the Cuban people, they may have been the recipients of what they were told they wanted, but have always been shut down from asking, wanting, or speaking out about something outside of Castro’s stage.

Citations:

1. Alter, Jonathan. "Taking Sides." Sunday Book Review of “The Man Who Invented Fidel” by Anthony Depalma. April 22, 2006. Accessed November 15, 2015. http://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/23/books/review/23alter.html?_r=0.

2. "American Experience: Fidel Castro," YouTube video, 1:49:38, posted by "Best Documentaries on Youtube," June 27, 2015. Directed by Adriana Bosch. PBS/WGBH, 2005, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LC4hNWzyCzU.

3. Assange, Julian. "Cuba to Work around US Embargo via Undersea Cable to Venezuela." WikiLeaks. July 16, 2008. Accessed November 22, 2015. https://wikileaks.org/wiki/Cuba_to_work_around_US_embargo_via_undersea_cable_to_Venezuela.

4. Chacon Marin, Francisco. "La Gran Decision (Memorias De Un Exiliado Cubano)" Raleigh, NC: Lulu.com, 2015. 498.

5. “Cuba: Castro’s Propaganda Apparatus and Foreign Policy,” Central Intelligence Agency (FOIA), November 1984 (Released July

2003): http://www.foia.cia.gov/browse_docs.asp?doc_no=0000972183.

6. Hampsey, Major Russell J. "Voices from the Sierra Maestra: Fidel Castro’s Revolutionary Propaganda." Military Review, November-December 2002, 93-98. Accessed November 13, 2015. https://server16040.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm4/item_viewer.php?CISOROOT=/p124201coll1&CISOPTR=234&CISOBOX=1&REC=2.

7. "Internet Y Conectividad: Preguntas Más Frecuentes." Empresa De Telecomunicaciones De Cuba S.A. Accessed November 23, 2015. http://www.etecsa.cu/?page=internet_conectividad&sub=datos_pmf#Internet.

8. Lakshmanan, Indira. "Cuba's Internet Dilemma: How to Emerge From the Web's Stone Age." Bloomberg.com. August 27, 2015. Accessed November 22, 2015. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-08-27/cuba-s-internet-dilemma-how-to-emerge-from-the-web-s-stone-age.

9. Marino, Mallorie E. "The Cuban Apparatus for Active Measures: Propaganda and Disinformation Against The United States." Cuba in Transition 21 (2011): 350-60. Accessed November 15, 2015. http://www.ascecuba.org/publications/annual-proceedings/cuba-in-transition-volume-21/.

10. Matthews, Herbert L. "Cuba Rebel Chief Is Visited in Mountain Hideout." New York Times, February 24, 1957, Front Page sec. Accessed November 15, 2015. http://www.nytimes.com/packages/html/books/matthews/matthews022457.pdf.

11. "Medios De Comunicación." Portal Cuba.cu. La Empresa de Tecnologías de la Información y Servicios Telemáticos Avanzados (CITMATEL). Accessed November 16, 2015. http://www.cuba.cu/categorias/medios-de-comunicacion/8.

12. "Meet the Press: Fidel Castro, April 19, 1959." You Tube. April 19, 1959. Accessed November 19, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CJvg8CzGVWo.

13. Nguyen, Ashley. "14ymedio's Yoani Sánchez: 'Technology Is an Incredible Ally for Independent Journalism in Cuba'" International Journalist' Network. November 10, 2015. Accessed November 16, 2015. https://ijnet.org/en/blog/14ymedios-yoani-sánchez-technology-incredible-ally-independent-journalism-cuba.

14. Powers, Shawn M., and Michael Jablonski. "Toward Information Sovereignty." In The Real Cyber War: The Political Economy of Internet Freedom, 155-179. Champaign, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 2015.

15. Press, Larry. "Cuban infrastructure investment – China won the first round." The Internet in Cuba: Applications, Implications and Technology. Accessed November 22, 2015. http://laredcubana.blogspot.com/.

16. Rodríguez Martinto, Jeniffer. "Divulgan Cifras Del Salario Medio En Cuba." Cubahora: Primera Revista Digital De Cuba. May 27, 2015. Accessed November 22, 2015. http://www.cubahora.cu/economia/divulgan-cifras-del-salario-medio-en-cuba.

17. Xalma, Cristina. Cuba: ¿Hacia Dónde? Transformación Política, Económica Y Social En Los Noventa: Escenarios De Futuro. Barcelona: Icaria Editorial, 2007.